Watch the concert via our live stream!

This concert will be available as a podcast and on CD.

Details will be posted when available.

Divine Majesty:

A glorious revival of 19th century synagogue music

Joshua R. Jacobson, Artistic Director

with soloist Cantor Peter Halpern,

Temple Shalom of Newton

Edwin Swanborn, organist

Elias Seidman, soprano

PROGRAM

PRELUDE

Mah Tovu Louis Lewandowski (1821-1894)

MUSIC FOR OPENING THE ARK AND

RETURNING THE TORAH

Torah Service Louis Lewandowski

Torah Service Salomon Sulzer (1804-1890)

Torah Service Samuel Naumbourg (1817-1880)

POSTLUDE — MUSIC AS MIDRASH

Min Ha-Metsar Jacques Halévy (1799-1862)

The Zamir Chorale of Boston

Following the concert, guests are welcome to remain for a half-hour “talk-back” with:

Joshua Jacobson, Artistic Director

Cantor Peter Halpern, soloist

Cantor Brian Mayer, soloist

Edwin Swanborn, organist

Cantor Louise Treitman, Zamir soprano

PROGRAM NOTES

BERLIN

Louis Lewandowski (1821-1894)

In 1833 a destitute orphan boy made his way from his hometown of Wreschen to the big city of Berlin, where he would be apprenticed to Asher Lion, cantor at the Heidereutergasse Synagogue. Within a few decades Eliezer Lewandowski, better known as Louis, would become one of the most influential figures in the history of synagogue music.

In Berlin his talent was quickly recognized. Thanks to the influence of Alexander Mendelssohn (first cousin of Felix), Lewandowski was admitted to the Berlin Academy of the Arts—becoming first Jew to be admitted to that school.

In 1844 Berlin’s Jewish community invited Lewandowski to organize and direct a synagogue choir. This was not to be the primitive improvised harmonies that were heard in most synagogues. This was to be a trained ensemble of men and boys who could read music. With this appointment, Lewandowski became the first full-time independent choirmaster in the history of the synagogue.

In that same year Michael Sachs was appointed Rabbi and one year later Abraham Jacob Lichtenstein was appointed cantor. Sachs, Lichtenstein and Lewandowski all sought a middle ground that would modernize the liturgy, while retaining the traditional elements.

On September 5, 1866 the New Synagogue of Berlin, the Oranienburgerstrasse Synagogue, was dedicated. With seating for 3,200 it was the largest synagogue in Germany, and it boasted one of the finest pipe organs in the city. Lewandowski would compose hundreds of pieces for services in this grand synagogue. His music for cantor, choir and organ was published and frequently reprinted and spread throughout the Ashkenazi Jewish world.

VIENNA

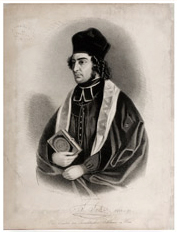

Cantor Salomon Sulzer (1804-1890)

Two hundred years ago, Vienna was the cultural capital of Europe, a political and commercial gateway between East and West, the seat of the Hapsburg dynasty and the Holy Roman Empire, the capital of Austria-Hungary, the city of Mozart and Salieri, Haydn and Beethoven, an exquisite and impressive city of magnificent palaces, idyllic parks, splendid theaters and concert halls, and, of course, the beautiful blue Danube.

In Vienna (and throughout Western Europe) Jews were beginning to leave the confines of ghetto life to participate for the first time in the cultural activities of the surrounding community. They joined their middle-class neighbors and attended concerts and operas in the new public theaters as well as soirées of chamber music in private homes.

Enter Salomon Sulzer. He was born in 1804 in the Austrian town of Hohenems, near the Swiss border. As a child he displayed a prodigious talent in music, and the Jewish community decided to appoint the 13-year-old boy as the official hazzan of their synagogue. But that appointment then (as now) had to be approved by the government. The Emperor Joseph II decreed that the boy could serve, but only after he had completed his education. So for the next three years, young Sulzer learned his trade. He apprenticed himself to a master hazzan in nearby Switzerland to learn the traditional Jewish chants. He also went to Karlsruhe to study the art of European secular music.

At the age of sixteen he returned to Hohenems and became the musical leader of the synagogue. But he would not remain in the sticks for long. The fame of this young prodigy quickly spread. After five years in Hohenems, an invitation came from Vienna to audition for the post of hazzan at the new and beautiful synagogue on Seitenstettengasse.

In 1824 the Jewish community of Vienna had finally received permission from the authorities to build a new synagogue for its steadily growing community. The community hired one of the most famous architects of Austria, Josef Kornhausel. A synagogue was built on Seitenstettengasse and dedicated in April, 1826. From the outside, the synagogue looks like one of many storefronts or residences in the area, but the interior was stunning and majestic. The sanctuary was oval-shaped, seating up to 550 worshippers. The women’s balcony had an unobstructed view of the sanctuary. There was a special balcony for the choir just above the ark. The furnishings and decorations were exquisite. The acoustics were excellent.

A new Rabbi was brought in to serve the community. Noah Mannheimer, a modern man, would adapt the ancient liturgy to suit the cultivated tastes of the Viennese Jewish bourgeoisie. When Sulzer arrived in Vienna he found a beautiful building, a sophisticated community, a liberal and well-educated rabbi, but a liturgical music that was in wretched condition. Sulzer wrote in his memoirs, “I encountered chaos [when I arrived] in Vienna, and I was unable to discover any logic in this maze of opposing opinions.”

Like Rabbi Mannheimer, Cantor Sulzer tried to find the “middle road” — a path that would preserve the traditions, yet cast them in a modern light; that would retain the essential traditional elements of Judaism, but clothe them in Austrian garb; that would please the older generation, and at the same time provide a idiom to which the younger assimilated Jews could relate. His singing attracted admirers from far and wide, Jews and non-Jews. His choir was considered by many to be the finest a cappella ensemble in Vienna. And his compositions were praised in Vienna’s press and soon were heard in synagogues throughout Europe and even across the Atlantic.

PARIS

Cantor Samuel Naumbourg (1817-1880)

Paris, after all, was where it all began. The seeds for liberal humanism had been planted by the industrial revolution, nourished by the enlightenment philosophers, burst open with the French Revolution of 1789 (Liberté, égalité, fraternité), and then spread throughout Europe by Napoleon. In 1808 Napoleon would declare, “…under the influence of various measures undertaken with regard to the Jews, there will no longer be any difference between them and other citizens of our empire.” Paris was not only a center of music, but also a center for freedom of thought, a place where Jews could feel at home.

Into this fertile ground came the young cantor Samuel Naumbourg. A descendent of a three-centuries-old cantorial family in Germany, Naumbourg arrived in Paris in 1843. Two years later, upon recommendation by the famous opera composer Jacques Halévy, Naumbourg was appointed to the post of Chief Cantor of Paris and was commissioned by the French government to arrange a new musical service to be introduced into all French synagogues. Halévy (1799-1862) himself had come from a strong Jewish background; his father had been a cantor and secretary of the Jewish Community of Paris. Naumbourg served ably as cantor at the great synagogue on Rue de Notre Dame, he collected and published traditional chants, introduced order into the synagogues of the French Republic, and he composed beautiful new settings of the liturgy for cantor and choir.

THE ORGAN

Traditional Jewish worship had eschewed the use of musical instruments. This was in part as a result of a rabbinic decree that since the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple by the Romans in 70 c.e. the Jewish people were to be in a state of mourning. But another factor was the perceived need to distinguish Jewish worship from Christian worship. And for centuries the organ had been associated with the Church.

But in the 19th century more and more synagogues were introducing the “king of instruments” into their services. Louis Lewandowski wrote, “The organ, in its magnificent sublimity and multiplicity, is capable of any nuance, and bringing it together with the old style of [Jewish] chanting will inevitably have a marvelous effect. The necessity, in the almost immeasurably vast space of the new synagogue, of providing leadership through instruments to the choir and most particularly to the congregation imposes itself on me so imperatively that I hardly think it possible to have a service in keeping with the times in this space without this leadership.” And yet, just two years before his death, Lewandowski was reported to have confessed, “I, who organized the music of the whole worship service and organized it indeed with the organ, I am myself in my heart of hearts an opponent of the organ in the synagogue.”

Salomon Sulzer was at first opposed to the use of the organ. His early published compositions are all presented a cappella. However his position seems to have evolved. In 1869 he wrote, “Instrumental accompaniment for the singing in the worship service should be introduced everywhere, in order to facilitate the active participation of members of the congregation in the same. … To provide the requisite accompaniment to this end, the organ deserves to be recommended, and no religious reservations conflict with its use on the Sabbath and holy days.”

Samuel Naumbourg had serious misgivings about the use of the organ, despite the presence of the instrument in his synagogue. In 1874 he wrote, “Another unfortunate innovation is the introduction of the organ in many synagogues. … I prefer choral singing over it. The organ can never be joined to our prayers and to our traditional songs without destroying their charm.” Yet when he published the third volume of his compositions in that same year, Naumbourg wrote that these liturgical settings could be performed “with an accompaniment of organ or piano ad libitum.”

– Joshua Jacobson